In a recent Los Gatan article, titled “Town’s effort to acknowledge earliest residents fraught with challenges,” journalist Drew Penner was attempting to shed light on the efforts of the Town of Los Gatos to acknowledge its less-than-inclusive telling of its own history. But the piece, which discussed how Los Gatos is seeking to correct that error by mentioning the “original inhabitants” through a ceremonial land acknowledgment, became tangled up with questions of tribal legitimacy.

Mr. Penner opines that there is disagreement over who should be acknowledged; he quoted statements by staff and Council members illustrating the confusion confronting Bay Area municipalities about what constitutes a historic Native American tribe and what does not. Often public agencies fear being labeled as “non-inclusive” or accused of “silencing Indigenous voices.” That was clear in the comments of Los Gatos’ officials. Rather than completing a thorough investigation, the Town seems frozen in fear of negative publicity. As a result, Los Gatos appears willing to allow any individual of Indian descent to claim territory and start demanding respect and compensation.

‘Los Gatos appears willing to allow any individual of Indian descent to claim territory and start demanding respect and compensation.’

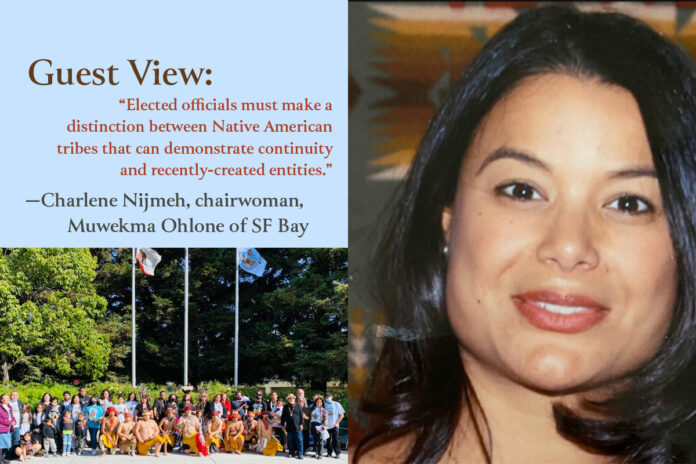

—Charlene Nijmeh, chairwoman, Muwekma

Correcting lies and misinformation is the only path towards justice. Creating new myths will only further injustice. All Indigenous voices must be welcomed in Indian Country. We are all battling to remedy injustice and preserve our culture. Federally-recognized—as well as unrecognized—tribes, individual descendants, newly-formed organizations, nonprofits and Indigenous activists need to work together to protect our sacred sites and fight for environmental, social and historical justice. This was something my grandmother—born on the Sunol Rancheria in 1911—taught me. I heard it from my mother, who served as chairwoman of our tribe. The message was echoed by our tribal elders—who enrolled with the Bureau of Indian Affairs under the 1928 California Indian Jurisdictional Act.

The Town’s elected officials must make a distinction between Native American tribes that can demonstrate continuity and recently-created entities. Tamien Nation never existed prior to December 2020 and was organized by Ms. Quirina Luna Geary around the time she resigned from her role as a councilmember with the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band. Indian tribes—federally-recognized or not—are sovereign “Tribal Nations” predating the United States. If any individual with an Indian ancestor could start a tribe of their own whenever they felt like it, there could potentially be thousands popping up, demanding attention from cities and institutions.

Muwekma, on the other hand, can demonstrate our links with the past. Phoebe Apperson Hearst and her husband, U.S. Senator George Hearst, purchased our Alisal Rancheria in the 1880s. Later, she funded the Anthropology department at UC Berkeley, inviting renowned anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber to interview our elders still living there. Our landless tribal community was included in the federal Indian censuses of 1900 and 1910, and the Special Indian Census of 1905-06. We were placed under the jurisdiction of Special California Indian Agents—and later, the Reno and Sacramento superintendents.

In 1910, Kroeber published vocabulary taken from our elders and included the term Muwekma, which means “the people.” John Peabody Harrington, a linguist with the Smithsonian Institution, also interviewed our elders (1925-1930). He, too, recorded the linguistic term Muwekma: the word was spoken by Maria de los Angeles Colos (Angela). Her parents married at Mission Santa Clara in 1838, and she was born on the Bernal Rancho in the Santa Teresa Hills in 1839. Angela later married a Clareño Indian named Raymundo Bernal/Sunol in 1873. She told Harrington, “The Clareños were much intermarried with the Chocheños [Indians from Mission San Jose]. The dialects were similar.”

In a Sept. 21, 2006 decision (Muwekma Ohlone Tribe v. Kempthorne), the Federal District Court for the District of Columbia affirmed our legitimacy stating, “The following-facts are not in dispute. Muwekma is a group of American Indians indigenous to the San Francisco Bay Area, the members of which are direct descendants of the historical Mission San Jose Tribe, also known as the Pleasanton or Verona Band of Alameda County (‘the Verona Band’)…From 1914 to 1927, the Verona Band was recognized by the federal government as an Indian tribe…Neither Congress nor any executive agency ever formally withdrew federal recognition of the Verona Band.”

Muwekma has been transparent and open, publishing genealogy and other records, so journalists, academics, and public agencies can do their due diligence. I call on any group claiming to represent a tribe that says it originally resided in the Los Gatos area to present legitimate documentation proving tribal status.

*The op-ed has been edited for length and clarity.