An older woman with blonde hair clutches grocery bags and scurries out of the Slavic Shop, the Saratoga Avenue store where South Bay residents come to buy Dworek Ukrainian borsch, potato and cheddar pierogis, and marinated herring filets.

The woman, who identifies herself as Ukrainian but declines to give her name, is visibly shaken. Russia just invaded her country hours earlier, after all.

“It’s terrible what’s happening,” she said in dismay, pausing for a moment in the San Jose strip mall parking lot. “I hate Russia.”

She quickly gets into her red Toyota Prius, backs up, and drives away.

Inside, the owner appears from the back, looking stressed.

“We’re still processing it,” he said. “I have friends that are under fire right now.”

He doesn’t want to say anything more, just yet.

Things are developing in rapid-fire succession on the other side of the globe, with ripples already slamming into our shores, here in the Los Gatos area…

Los Gatos resident Natasha Lyukevich had been looking forward to her usual ukulele lesson with 35-year-old Sergio Peshko, who’d been quite successful at teaching her 11-year-old son Colin Kennedy the Hawaiian instrument.

Like everything else during the pandemic, this was to happen virtually. The difference was this music tutor wasn’t down the road in Saratoga or Willow Glen—Peshko was located in Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital.

“I can’t teach you today because I have a war,” he said, recalling the message he sent Lyukevich Feb. 24, in a Skype interview with the Los Gatan. “I was worried about the situation, because I don’t know what to do.”

He was supposed to be living in China, where he’d been working as a guitarist. It’s where his girlfriend lives. But after the coronavirus broke out while he was back in Europe, he couldn’t return.

Instead, Peshko has been working as a sound engineer for a Crimean broadcaster, but he also enjoys guiding learners all over the world toward musical proficiency, including with the ukulele.

They often expect it’ll be a cinch to learn to play what looks like a simplified guitar, he muses.

“Some of them think ukulele is an ‘easy’ music instrument, but it’s not so easy,” he said. “I also like to prepare for lessons, create some tasks, search some new songs, create materials for lessons.”

Peshko also taught Lyukevich’s older son electric guitar, too.

He knew conflict might be imminent. But when it actually arrived, he was still shocked.

“At the morning, I just heard just big Boom!,” he said, recalling the moment he realized the invasion had begun. “The sound of explosion was not so close to me, it was, I don’t know, maybe, 20 km or 10 km (away).”

Peshko, who’s been living with his parents and cousin in the Troieshchyna neighborhood, said he was so worried he couldn’t eat.

“The whole day we just stay home,” he said. “We started to collect our documents, to collect some important things—some essential clothes—and just monitored the situation inside the country.”

That night Peshko and his family were summoned to the bomb shelter.

“The city outside was silent,” he said. “I heard just a few times the (Ukrainian) air forces was flying near our district.”

Eventually, they were told they could return home. He tried to sleep, but sleep was hard to come by.

They made the decision to flee to the countryside where Peshko’s grandmother lives. They wanted to get out of Kyiv before the trip became impossible. At that point, traffic wasn’t even that bad, he remembers.

“We went to the village because, who knows? Maybe the Russians will attack the roads or something like that,” he said. “I was just praying to God that we won’t have any troubles on the road.”

They passed Ukrainian army soldiers and tanks, and made it to their destination without incident.

Peshko was struck by the long line of fellow countrymen he saw, in the neighboring town, who were trying to sign up to defend the country.

He now wonders if he’ll have to shoulder a weapon, too, if that’s what it comes down to.

“I’m not an army man; I don’t have any experience with weapons,” he said. “I hope I won’t do this. I hope. But I can’t say, Will I?, or not. I hope I won’t.”

At this point, he still has access to the internet—and was able to bring his instruments with him—but he says his Los Gatos student will just have to wait to reschedule.

“Technically, I can do my teaching,” he said. “But, you know, the mood and the emotion, it’s, like, not so well to do this. And the situation is, like, so quick-changeable.”

Still, Peshko sees a silver lining.

“The US, and all European countries, they understood who is Putin, what is the Russian fascist propaganda machine,” he said. “They finally realized. This is good part.”

On a moment’s notice

Kennedy, who the Los Gatan previously profiled when he was recognized for his accordion-playing skills, has been studying double bass. The last song a tutor began teaching the boy on his youth-sized stringed instrument was “We Will Rock You,” by Queen.

Unfortunately, this instructor, too, is in Ukraine—under attack. Their last lesson was on the Sunday before the invasion.

“He’s learning complex work,” said Igor Levchuk, 23, from his home in Dnipro, about seven hours southeast of Kyiv, of his Los Gatos student. “We have scales. We have songs. We have exercises.”

Levchuk’s been assisting Kennedy with his Daves Avenue Elementary music class homework, but on Feb. 24, his life was turned upside-down.

“We have one military building and airport that was bombed in this day,” Levchuk said. “My first reaction was to calm down. I was really scared.”

Unlike Peshko, who’d been analyzing online reports over the past several weeks to gauge the likelihood of a Russian invasion, Levchuk says he mostly stays away from political news.

“I’m in music,” he said. “So, I don’t watch news about this conflict.”

After all, he’s had his mind on another upcoming event—tying the knot with his fiancé.

“I hope that we (can still get) married in August this year,” he said. “We just started to plan our wedding day.”

It’s what he thinks about when he hears of people joining the army or territorial defense force.

“I’d like to go to the military, but I can’t do this,” he said, explaining his fiancé’s parents don’t live in the area and he wants to protect her. “I just can’t leave my girlfriend alone.”

Every day he asks himself if they should’ve attempted to escape the country earlier. Now, he couldn’t get out even if he wanted to, since the government is preventing most men from crossing the border.

In their new reality, they live by curfews and race to the bomb shelter in the subway at a moment’s notice.

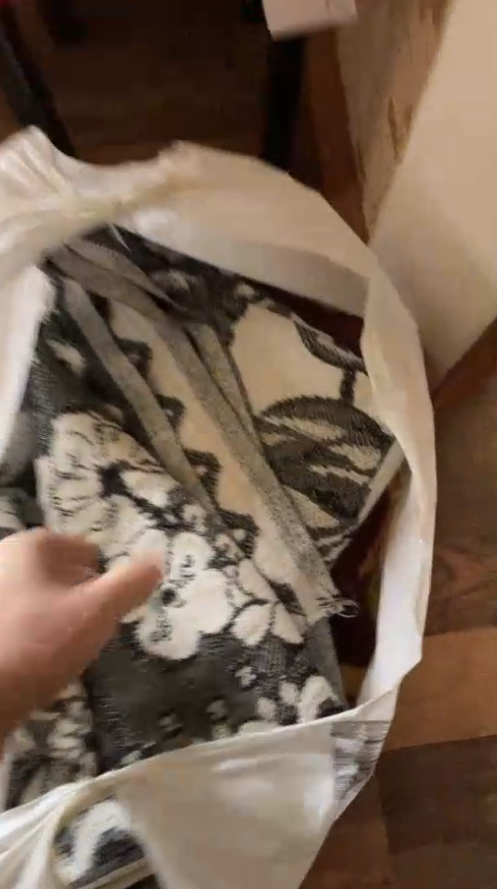

After getting back from one such excursion, he showed the Los Gatan the go-bags he and his girlfriend bring with them. It includes blankets to sit on, since it’s the middle of winter—hovering around 32 degrees—and is pretty cold in some spots down there.

But Levchuk still managed to return home shortly after the interview was originally scheduled to begin. He said his plan for the day was to call a friend who works as a volunteer for an organization that distributes food.

“We just protect our country from Russia’s military,” he said. “A lot of people in Ukraine, they need help—and no one wants this war.”

Levchuk was clearly touched—far above and beyond the financial aspect—by the pre-order of 10 lessons Lyukevich had put in, to ensure he could receive it while it was still possible to access money through the banking system.

Fearing for family, friends

Aleks Rombakh, 15, is in her first year at Los Gatos High School.

She was born here in the South Bay, but her Ukrainian citizenship means the world to her. She explains, proudly, that when her ancestors were forced to escape Bulgaria back in the day, the country came to their aid.

“They escaped to Ukraine,” she said. “They gave them shelter.”

She’s close with a distant relative, who remains in Odessa. He’s Rombakh’s fourth-cousin, but their parents grew up in the same house together during WWII, so the families have always been close.

He told her, “Everything’s fine.” But later, she found out he was putting on a good face for her.

“I’m really scared for him,” she said. “He means so much to me.”

His mom’s been reporting food shortages—even at the more expensive grocery stores.

“The shelves were all empty,” Rombakh said. “All she could get was a loaf of bread.”

Just days ago, her mom, Olga Mavrody, who owns a Los Gatos accounting business, was planning a trip to Ukraine—envisioning restaurants, beaches and nightlife. Now that’s out the window.

“We’re completely stunned,” Mavrody said of the invasion. “What has happened with Russia—it’s just unheard of.”

A few hours earlier, at breakfast, her own mom had shared about how much the situation reminds her of living through the Nazi invasion.

Mavrody confirms their friends and family have been through the wringer in Ukraine, already.

While her aunt, in Odessa—who’s in her 70s—seemed to be taking everything in stride, another friend there isn’t quite so even-keeled.

They’re shooting at my building, read the text she received Sunday from the woman. Can you get me out of here?

So, Mavrody started researching how her friend could seek asylum.

The same day, she spoke with another extended family member who reported her adult son had successfully exited the country—passing through Moldova and into Romania—right before the border closed.

The war isn’t just affecting local Ukrainians, Rombakh notes. In fact, one of her classmates, whose family immigrated from a former Soviet state, wonders how it might affect their loved ones, too, if war continues.

Three days into the invasion, a couple of Azerbaijani women, who asked to remain anonymous, were at the Slavic Shop, picking up some Eastern European-style cookies.

“We stand with Ukraine,” one told the Los Gatan.

Meanwhile, at least one social justice group in the region has cautioned people not to discriminate against Russians, just because of the actions initiated by Vladimir Putin.

On Feb. 23, Henry Patland, the founder of Patland Estate Vineyards, who lives in Los Gatos with his wife Olga, posted a photo on Facebook where he’s drawing a sword while garbed in a blue robe. A Ukrainian flag is superimposed at the bottom.

“Standing with you and Olga!” commented Elena Mosko, the founder of Los Gatos-based Globiana, Inc., a teaching platform that does intercultural training.

“Unless western civilization stands up to Russia United now, it will give a clear signal to Russia and China that they control the world!” Patland wrote.

Nothing to joke about

Back at the wildcat statue at LGHS, Rombakh says she understands that people often cope with tough situations by using humor, but says she wants her peers to understand now’s not the time for crass remarks.

“They should know that it isn’t something to joke about,” she said. “It feels so weird seeing people make jokes like, ‘Oh, WWIII is starting.’”

Rombakh hopes to do some outreach at her school, noting she’s looking into contributing an article to El Gato, the student newspaper.

But while she knows Ukrainian refugees—and those amidst the shelling—will need plenty of financial support, she reports she’s already identified at least one scam fundraiser in her online feed.

At least people are starting to learn about Ukraine, she reflects.

“Most people didn’t even know it existed,” she said, adding she takes issue with a teacher telling the class Putin’s war started this week, since hostilities with Russian-backed fighters have been ongoing for years. “At least my homeland is not brushed off as, ‘Oh, that’s just Russian.’”

Finding ways to help

Anna Usatenko, 31, is a Santa Cruz Mountains resident, living in the community of Bonny Doon. During the CZU Lightning Complex fires, it was Los Gatos that provided her refuge from the flames, as she moved here temporarily.

On Sunday, the day Putin put his nuclear forces on alert, the Ukrainian said her thoughts were now consumed by a different disastrous situation—war in Ukraine, and her loved ones caught up in it.

When Putin’s “special operation” commenced, she learned the news before her friends over there did. She frantically reached out to her contacts in Ukraine to make sure they were up to speed about what was going on. It wasn’t long before they saw evidence, first-hand.

“My sister lives in Kyiv,” she said. “It was explosion there, as well.”

Usatenko couldn’t sleep all night. The following morning, she decided to take the day off from her job as a quality engineer for a software company.

“I was texting with my friends and my relatives,” she said. “I wasn’t able to work.”

She started to post on social media, including encouraging her Russian friends to disseminate truthful updates to their followers, to combat the narrative coming out of the Kremlin.

“It’s difficult for me,” she said. “I’m always thinking about this situation and how I can help. I am helping sharing information, sharing petitions.”

She has a friend who lives in Irpin, a northwest suburb of Kyiv, for example. At press time a 40-mile long Russian convoy was on its way to the capital city.

“We are hoping that Russian people who live in Russia, they can stop Putin,” Usatenko said. “They don’t believe that there is war in Ukraine.”

If Russia decides to press on with its invasion, it will get more than it bargained for, Usatenko predicts, recalling the Ukrainian spirit so evident during the Euromaidan protest movement of 2013-2014.

“Ukrainian people are free people,” she said. “They don’t like when someone’s ruling their lives.”