I was at the tippy-top of Montara Mountain on a clear day last month near telecommunications equipment—Mavericks to the south, Pacifica to the north—when a call beamed in to my cellphone. It was Roshan Gudapati, the Silicon Valley investor—perhaps best known for co-founding Chiplogic Technologies—calling from India, wondering why I was trying to reach him.

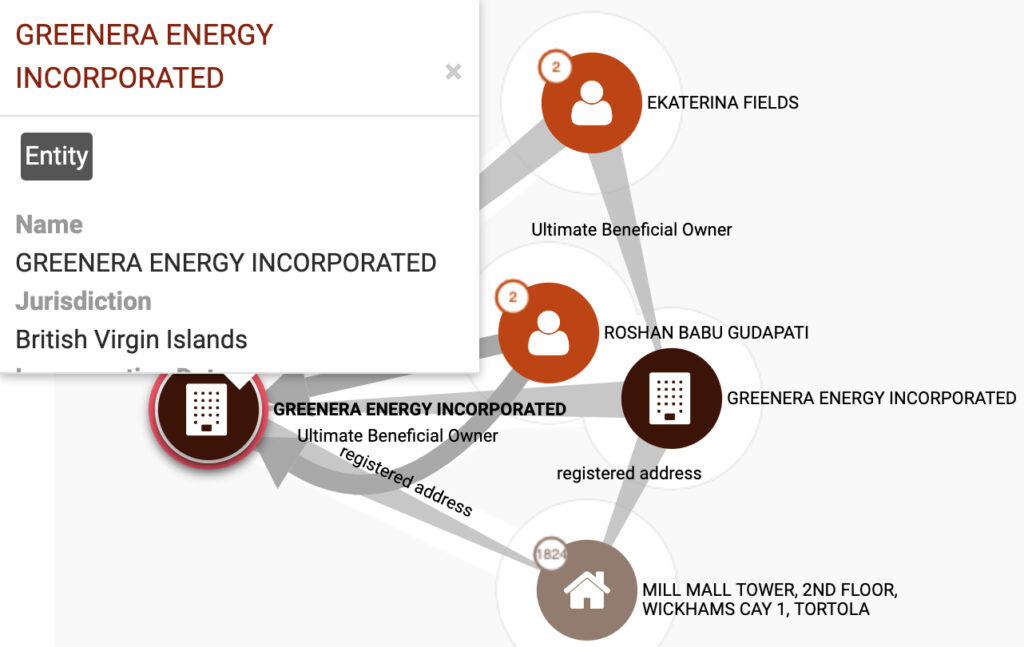

I informed him that his name—along with his residential address in Saratoga—had, days earlier, been made public, as part of the Pandora Papers, the latest data dump by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. The group’s Offshore Leaks Database aims to pull the cover back on the shadowy world of global finance. I wanted to know what the deal was behind the company he’d registered in the British Virgin Islands—Greenera Energy, Inc.

Gudapati said he’d done nothing wrong, and that there was a perfectly valid explanation. I asked about the woman whose name popped up alongside his as a fellow owner of Greenera—a Russian influencer living in London. Gudapati claimed he’d never heard of her. But, he said, if I was interested—after he returned to Silicon Valley—he’d be willing to explain the particulars about the clean tech startup that had landed him in the database. I told him I’d send a link to his node on the ICIJ’s digital map. Then, I hiked down the mountain.

MURKY FINANCIAL WATERS

Matti Kohonen, the executive director of the Financial Transparency Coalition, says the Pandora Papers offer a glimpse into the secretive world of global capital. The organization contends that this sort of information should be freely available to the public.

“The term ‘tax haven’ comes from the era of piracy, where certain sea ports (either Caribbean or UK south coast, or US east coast) were ‘pirate havens,’” he said. “The term then developed to mean a place to ‘save,’ or ‘shelter,’ from modern authorities—like tax authorities or corruption watchdogs.”

But Kohonen notes if wealth held offshore—like dividend income, or capital gains—is declared to the IRS, it might actually be completely legal. Plus, these days, American jurisdictions like New Jersey and South Dakota are emerging as significant tax havens themselves, he adds.

Under the prior Paradise Papers leak, former Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney was linked to an arms dealer, and the chief fundraiser of the country’s current prime minister, Justin Trudeau, was separately implicated. Thanks to the earlier-yet Panama Papers release, Icelandic politician Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson resigned from his job as prime minister amid outcry over money sheltered abroad. That leak also included six members of the British House of Lords, several of whom donated money to David Cameron, who was prime minister at the time. Deng Jiagui, the brother-in-law of current General Secretary Xi Jinping, was found to have two shell companies in the British Virgin Islands, although they weren’t active by the time Xi became General Secretary, according to American Public Media’s Marketplace.

The Pandora Papers reveal the real owners of more than 29,000 offshore entities, who hail from more than 200 countries and territories, says Fergus Shiel, the ICIJ’s managing editor.

“Shell companies might sound like serried ranks of periwinkle pickers fathoming the mysteries of frail and radiant whelks of the sea, but, in reality, they are one of the most harmful things ever fashioned: a multi-trillion dollar drain on the foundations of good governance by corporations that exist only on paper and are used to disguise business ownership,” he said, explaining why he believes leaks like Pandora are necessary. “We are fortunate that technology allows us to ride huge waves of information.”

According to Shiel, there are many legitimate reasons to have offshore accounts—but plenty of nefarious ones, too.

“Creating a world where financial incentives for conflict, wars, human rights abuses and violence are non-existent ought to be a goal for us all,” he said. “Dark money flows are at the heart of countless evils, autocracy and global inequality.”

While the U.S. is looking at cracking down on opaque financial flows in the wake of Pandora, Shiel isn’t exactly counting on it.

“The Biden Administration moves are encouraging, but many obstacles remain,” he said, pointing to the way the internet and cryptocurrency have just made things easier for those who don’t play fair. “Big banks, law firms and other powerful groups often oppose stronger transparency rules and tougher enforcement against offshore abuses.”

For example, he points out, the U.S. refused to join a 2014 agreement supported by more than 100 jurisdictions, including the Cayman Islands and Luxembourg, to require American banks to share information about foreigners’ assets.

“Much more needs to be done to stem dark money flows,” he said. “One important first step would be mandatory registration of company ownership across the globe in publicly accessible, easily searchable and free databases.”

IN GOOD COMPANY

Gudapati joined the array of local residents added to just such a database through previous ICIJ leaks. There were at least 18 other Los Gatos addresses featured in the so-called “dark money” data dumps. Because the information obtained by the ICIJ is limited, it isn’t necessarily up-to-date. Some people may no longer own homes in the Los Gatos area, or their shell companies may have been shuttered. As part of the Paradise Papers release, Bent Torp Jensen of Belvale Drive in Los Gatos was revealed to have been a shareholder in Malta-based Baltic Investment Holdings, Ltd.; another Los Gatan, Michael Lamendola, of the exclusive Arroyo Rinconada Community along Rio Vista, was listed as a director of Seawater Systems, Ltd., also based in Malta; Rick Van Nieuwenhuyse, of the Via de Tesoros neighborhood in Los Gatos, was listed as a president of NovaGold Resources (Bermuda), Ltd., which was, perhaps unsurprisingly, based in Bermuda. While president and CEO of Novagold Resources, Inc., Van Nieuwenhuyse helped the company secure “world-class” Arctic mineral deposits, according to Mining News North.

Gudapati’s residence joined at least 32 other Saratoga locations previously published in ICIJ leaks. That included Walter H.J. Timmerman, who is listed as a director and legal representative of Malta-based Eclectic Services Ltd.; Charles Yen-Chia Tzeng, described as an intermediary for the Samoan-registered Alpha Investment Holding, Ltd., with a home along Vallejo Drive; and Jeff Boldt of Heath Street, who was named as the president of Solaris Assurance, Ltd., supposedly located in Bermuda.

PATENT LAWYER NAMED

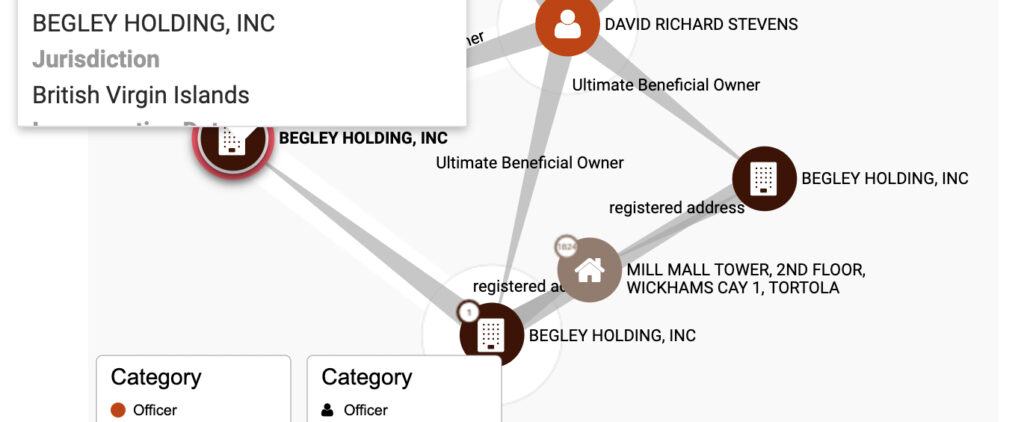

So far, with the Pandora Papers, Gudapati appears to be the only new Saratoga addition to the Offshore Leaks club. However, there is a fresh entry from Los Gatos—a lawyer named David Richard Stevens. He works at Stevens Law Group in San Jose, which, among other domains, specializes in keeping corporate information confidential.

“Our trade secret experts are able to help create a trade secret program to identify, establish and protect a company’s valuable secrets,” the firm’s website states. “This includes proper company policies, procedures and safeguards to protect their valuable trade secrets, and to also manage which company innovations are kept secret or relinquished in favor of published patent applications or issued patents.”

There was no response to multiple requests for comment from Stevens, who owns his Auzerais Court residence (associated in the Pandora Papers files with Begley Holding, Inc.—listed at one point as being “in penalty”) with his wife Ekaterina Stevens.

But it was a different Ekaterina who created the most mystery surrounding the local Pandora Papers revelations.

THE BEAUTY QUEEN

Moscow-born Ekaterina Parfyonova would skyrocket to fame as a child actor with her role in the 1986 film “Higher Than Rainbow.” She was named Russian Miss World at age 17, according to IMDB. She married Washington lawyer Richard Fields and won a £3.3m divorce payout—but held out for more. She moved to London, becoming a noted philanthropist and mining investor.

On the same day Ekaterina Field set up her company Higher Than Rainbow Productions, Ltd., in the British Virgin Islands—March 7, 2017—she also became an owner of Greenera Energy, Inc., according to ICIJ data. It was one of the things I was most curious about, since Gudapati said her name didn’t ring a bell. But he said he’d look into it.

After Gudapati returned from his overseas travels, he sent me a text at the beginning of January.

“Based on your questions to me about a Ms. Fields and her association with Greenera, I had contacted our registered agent for clarification as I wasn’t aware of such a person or any relationship with Greenera Energy,” he wrote. “Here is the message I received from the registered agent. Hope this clarifies things. Regards, Roshan.”

The attachment, sent Jan. 4, was in the form of an image depicting text mimicking a basic typewriter font.

“Please note that according to our records and the BVI Registrar of Companies, there is only one company registered with the name Greenera Energy Incorporated,” was the apparent agent’s reply. “It is not possible for two BVI Companies to be registered here in the BVI with the same company name, perhaps the Company was registered in another jurisdiction.”

Ms. Fields has no association with Greenera whatsoever in its files, the official added.

“Also, our records indicate that Ms. Fields is registered in our database with a BVI Company that was registered by our office, however the company name is not Greenera Energy Incorporated and we are no longer the registered agent/office of the Company.”

The Los Gatan reached out to Ms. Fields for clarification but did not receive a reply.

When I spoke with Gudapati on the phone two days later, he sounded genuinely mystified about the whole situation.

“I really appreciate you alerting me,” he said. “I had not heard of this ‘Pandora Papers’ before talking to you on the phone.”

Gudapati added he would’ve never thought to search his name in the ICIJ database.

“To me it looks like somebody made a mistake somewhere,” he said.

Gudapati said he was happy to go into details—even with a journalist—in the interest of transparency.

“My thinking is very simple,” he said. “If I haven’t done anything wrong and I have nothing to hide, what do I have to lose?”

GREEN ENERGY VISION

Gudapati worked for about a decade as a software engineer at Cadence Design Systems. He co-founded Chiplogic with a friend, producing semiconductors and software, developing operations in India and the United States.

“We actually ‘bootstrapped,’” Gudapati remembered fondly. “It was a bit of a struggle, you know? We made a lot of sacrifice.”

In 2000, Analog Devices Inc. announced it would acquire their company via a $100 million stock deal.

“We had a good outcome,” Gudapati said. “Subsequently, I worked for a number of years at Analog Devices.” He also started investing in other start-ups.

While in the process of building a team to get another software company going, Gudapati was introduced to a professor who suggested he invest in solar (photovoltaic, or PV) power plants in Greece.

“We looked at the tariffs and the licensing, and it sounded like a good thing to do,” he said.

The idea was to begin with small proof-of-concept facilities in Greece, and then expand throughout Europe. It would be a pretty complicated endeavor, on paper, so they approached Silicon Valley-based Structure Law Group about how to organize the corporation. Together they created Fusive Capital Select Partners in the United States as a way to put money in. And they ended up with two power plant properties in Greece, each set up as separate entities.

A British Virgin Islands shell company was suggested as a way to connect the two parts, and to allow investors around the globe to come on board.

“We were advised on a structure by this corporate lawyer and accounting firm—how we can be in the U.S. and have overseas investors,” he said. “All of that never panned out.”

That’s why the whole Ekaterina thing gets to him. According to Gudapati, they never managed to secure any investors in London.

Nevertheless, they negotiated power-purchase agreements, built a small solar plant in Florina, Greece, and began working on a second, larger, electricity generation site nearby.

“It was a long, long painful process,” Gudapati said, recalling the hoops the team had to jump through. “It all sounds fine and dandy, but in reality, there’s lots of bureaucracy.”

Greenera took an innovative tack, mounting PV panels so they rotated on a column to follow the sun, capturing more of its valuable rays, at the Florina location. And they brought in power lines to the land acquired for the planned facility. But their dreams of easy success were dashed by the Eurozone Crisis—as Greek authorities started demanding stricter terms. The government said it couldn’t come up with the cash to keep up its end of the bargain, he recalled. At first, they were getting around Euros 0.36 / kwh. Suddenly, that began to drop. Bad timing.

But the expenses continued to roll in—for plant upkeep in Greece, taxes in the U.S., and for the BVI “passthrough” entity, on top of everything else.

“We have to continue to pay the lease on the land, and obviously the corporate expense,” Gudapati said.

It would have cost millions of dollars to realize the second plant.

“The math was not looking good,” he said.

They decided to sell.

A party interested in the under-construction second plant emerged in 2012.

“Just when we were about to sign the deal, basically the Greek government announced even more punitive changes to the PV policy,” he said. “The buyer backed out.”

Gudapati says their licenses remained valuable, and despite taxes costing an arm-and-a-leg, the price of solar panels was dropping dramatically. In the end, they were able to sell the second license in 2018-19 at a loss.

To this day, they still operate the couple-hundred-kilowatt Florina plant, which brings in some revenue each year.

“This one is actually making money,” he said, although he notes it’s not much to sneeze at. “It frankly doesn’t move the needle for me.”

To Gudapati—who would rather focus on the development of the other tech and logistics start-ups he’s involved with—it’s more of a hassle than anything. This past year he considered whether it might be worth simplifying things and shuttering his Caribbean shell company altogether.

“It’s pretty expensive paying for the accountant—and paying the fees at every level,” he said, although that idea is counterbalanced by the thought that it might be easier to sell the remaining power plant business as-is. “Every time we want to wind down, there is a buyer that is interested.”

And so, Gudapati keeps a toehold in the Virgin Islands.