As Santa Clara County lawmakers prepare to approve new political boundaries, some local politicians are raising complaints about the process.

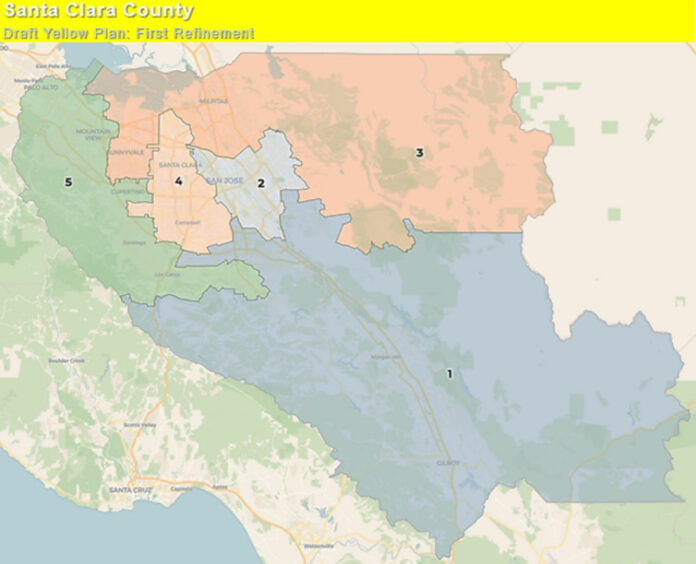

The Board of Supervisors voted 3-2 in November to advance a proposal for redistricting the county’s five political boundaries, choosing the so-called Yellow Map over two other options. Supervisors Mike Wasserman and Joe Simitian voted against advancing the map.

If approved, the map will move Almaden Valley and Los Gatos from District 1 into District 5 and eliminate Sunnyvale from being split between Districts 3 and 5, and move it wholly into District 3. It will also retain majority-minority Asian and Hispanic districts. Supervisors are scheduled to discuss the map during a Dec. 7 meeting.

As the board nears a decision on the once-in-a-decade process, there are lingering questions about the map created by a coalition of South Bay civil rights and labor organizations. Opponents of the map, including the Santa Clara County Republican Party, claim it’s gerrymandering meant to reduce conservative power in District 1. Some have also argued the process is tainted by conflicts of interest because two supervisors—Cindy Chavez and Susan Ellenberg—support candidates in the District 1 election.

“It’s clearly politically motivated,” said Johnny Khamis, a former Republican running for the District 1 supervisor seat. Khamis and another candidate in the race, Los Gatos Vice Mayor Rob Rennie, would theoretically be excluded because they’ll no longer live within the new district boundaries.

Khamis said he’s considering legal action if the county approves the map, citing his ethical concerns about Chavez and Ellenberg. He said he believes the map is gerrymandering and that it doesn’t comply with state and federal requirements, noting it has a high population deviation—meaning the population difference in districts is not equal—and that its boundaries are not compact.

Diluting voices?

Other South Bay politicians decried the map earlier this month, saying it will dilute Asian-American voting power. Palo Alto Councilmember Greg Tanaka, who is running for Congress, said the map will fracture the San Jose Vietnamese vote by splitting the population into several districts.

“On the county side, it seems like some of this is being done for political reasons, not necessarily for representation reasons,” Tanaka said.

San Jose City Council candidate Bien Doan agreed, calling the county map racist and discriminatory—but could not provide any specific examples of how it would split the Asian community.

The map preserves a majority of the minority Asian-Pacific Islander population in District 3, according to county data on the redistricting proposals.

Richard Konda, executive director of the Asian Law Alliance, said the Yellow Map, if approved, would mean District 3 contains all of Sunnyvale, making it a strong Asian American district.

“I strongly disagree that the (Yellow) Map dilutes Asian American voters,” Konda said. He added that the Alliance has submitted maps and recommendations on the state and assembly level in previous redistricting, but this is the first year it’s submitted a map for the county. He said the process of submitting a map is more efficient than submitting comments.

Jeffrey Suzuki, head of the Los Gatos Anti-Racism Coalition, said he doesn’t see how the map will harm Asian Americans in District 5. He claims Republicans oppose the map because it will rearrange political boundaries that have allowed wealthier white residents in places like Los Gatos and Almaden Valley to politically dominate District 1.

“If you don’t dilute those Latinx votes down in South County, then (Republicans) don’t win,” he said.

It’s not unusual for special interest groups to provide input during a redistricting process, including submitting maps.

Jeffrey Buchanan, director of Silicon Valley Rising Action, said the organizations that helped create the Yellow Map submitted other maps in previous redistricting efforts on the state and assembly level. This is their first time submitting local county maps.

Terry Christensen, a political science professor at San Jose State University, said it may be easier to submit maps now thanks to software that allows virtually anyone to draw up proposals for new political boundaries.

“It doesn’t take as much work as it would have done even 10 years, and especially 20 years ago,” he said.

Christensen dismissed Khamis’ claims of gerrymandering.

“I think there are really good arguments for the way that map is drawn,” he said, noting as examples Almaden Valley and Los Gatos have more affinity with communities of interest in District 5 than Gilroy and Morgan Hill in District 1.

Buchanan said the federal Fair Maps Act forbids redistricting to take into consideration where candidates or incumbents live. Silicon Valley Rising Action, Asian Law Alliance, San Jose/Silicon Valley NAACP, Latino Leadership Alliance and La Raza Roundtable support the map.

Buchanan said the coalition that created the map engaged in extensive dialogue with county residents to figure out how to keep communities of interest together. He said organizations such as the NAACP and the Asian Law Alliance have been involved in redistricting work for decades.

“To say it’s unprecedented for historic civil rights organizations to engage in a discussion about how redistricting lines are drawn is just a ridiculous claim,” he said, adding he has his own ethical concerns about candidates such as Khamis engaging so vocally in the redistricting process.

Potential conflicts

Khamis believes there’s a conflict of interest in the redistricting process because Ellenberg and Chavez have supported candidates in the District 1 election—Santa Clara County Board of Education President Claudia Rossi and Morgan Hill Mayor Rich Constantine, respectively—who would benefit from him being excluded.

“I don’t like to gloat, but I think I’m the frontrunner,” Khamis said, citing his war chest of nearly $100,000, according to campaign finance records filed in October. “You take out the frontrunner and what’s left? The people who are being supported by two of the supervisors.”

Asked if she should have recused herself from the vote, Ellenberg said redistricting is one of her core responsibilities. The board is not supposed to consider how redistricting will affect political candidates or incumbents. Ellenberg said she followed that rule.

“I looked at what was brought forward to me and listened to the public comments, and I’m not thinking about candidates or incumbents or political races of any kind,” she said.

Chavez’s spokesperson Beth Willon said the supervisor is not available for comment.

Political candidates aren’t barred from moving addresses to stay in the District 1 race, Christensen added.

“Johnny Khamis could always move to Morgan Hill,” Christensen said. “That’s always an option.”

Khamis acknowledged he could still run if he moved. But he said the new district won’t have his political bases of support, including Almaden, Blossom Valley and Vista Park.

“I could still run, but would my campaign be weaker? Most likely,” he said. Asked whether he intends to move to remain in the race, Khamis did not answer. Instead, he said, “I will not allow these people who want to gerrymander our voices to win.”

Rennie, who would also be excluded from the District 1 election if the map is approved, said he would consider staying in the race if he can remain in Los Gatos. He said it would be bad form to leave the town before his term is out.

“It’s disappointing to be kind of tossed out of the race,” Rennie said, noting he may wait to run for a supervisor seat in his new district in 2024.

Copyright © 2021 Bay City News, Inc. This story was originally published by San Jose Spotlight.