A tractor-trailer pulls onto the shoulder at the foot of the Santa Cruz Mountains near Morgan Hill, at dusk on Oct. 12, across from a fresh deer carcass where insects and amphibians sing their evening songs.

The driver, carrying something akin to a lunar crawler or oil sands equipment, pauses for a moment to revel in the fact that, while in an utterly rural landscape, he’s just a short distance from Apple Inc.’s global headquarters.

“New York,” he says, revealing his destination point, confirming that, following in the footsteps of many in the tech workforce in recent years, the four-axle Oshkosh machine is moving out-of-state.

It’s the third firefighting vehicle the Katz brothers have had to sell to pay for their ongoing legal brawl with the Santa Clara County Planning and Development Department.

The pair came to national attention in an Associated Press article about their efforts to respond to the 2020 CZU Lightning Complex Fires. State resources were stretched thin, and they appeared on scene to protect homes in Bonny Doon, a village north of Santa Cruz, long before Cal Fire crews arrived.

More than 900 homes were destroyed in the converging blazes.

Back then, they brought a single small fire truck, which they were later able to sell to afford the one now being sent back east.

Joe Christy, founder and president of the Bonny Doon Fire Safe Council, says he remembers hearing about the Katz brothers’ contributions, noting it was the private brigades that led defensive maneuvers during the three days they awaited Cal Fire.

The Katz brothers could’ve brought another truck, too—a more powerful model—had they not sold it off to cover legal bills in a protracted battle over grading they say they did, in part, to create a fire break on a newly-acquired property during the Loma Fire.

“If we had a second fire truck, we could have saved more homes,” Jesse Katz said. “We just didn’t have the resources—which I would’ve had if it weren’t for our legal problems with the County.”

Jesse, 44, was still covered in soot from the CZU response when he got a call from a Santa Clara County official. A Board of Supervisors aide told him an agreement they’d struck to pause enforcement had fallen apart. The County was going to strong-arm them.

And now, as a third fire truck disappeared into the night on the back of a semi, Jesse mused that he hopes it’ll find a new life protecting against forest fires in upstate New York, perhaps even across the border in Canada.

‘I don’t think what the County is doing should be allowed to happen under cover of darkness’

—Jesse Katz

Battle Lines

In the end, the Planning Department got what it wanted—a verdict that upheld stiff fines against the brothers with a healthy collection of military surplus vehicles in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

But the way in which the case against Jesse and his sibling Rob, 33, played out raises questions about practices employed by the Silicon Valley agency’s code enforcement officers and lawyers, as well as its transparency record, and suggests a willingness to disregard evidence to win prosecutions.

“I don’t think what the County is doing should be allowed to happen under cover of darkness,” Jesse said.

From the County’s perspective, the case is an example of the enforcement process working: a complaint from a neighbor leads to a visit from an official who orders the Katz brothers to stop moving large amounts of earth, and citations for violations are issued (for illegal cuts and fills amounting to millions of pounds of soil), then amended, as additional information emerges. Some are eliminated as the brothers argue their side of the story, but others remain, and the brothers must pay up.

The County levied 17 violations against the Katz brothers. After telling their side of the story, 11 were removed. Then, upon appeal, two more were deleted. With just four left, the County is still seeking more than $282,200 in fines—more than the original value of their sprawling property.

During an administrative hearing, the Katzes claimed they weren’t properly served with a Notice of Violation for some infractions, and said the County told them this would allow them to seize their land if they didn’t sign a compliance agreement.

“We asked repeatedly to have a copy of the NOV,” Rob testified. “They refused. We appealed to the Board of Supervisors, saying, ‘Can you please investigate this and show us if a NOV was sent?’ We’ve always maintained the mindset that, like, maybe we messed up, maybe we missed something. We’re human. But, in this instance, the error was on their part. And they lied about it—and then they doubled-down.”

Broader Issues

It’s not the first time County Planning has caused major headaches for Santa Cruz Mountains residents in wielding their code enforcement powers.

For years, the Planning Department has relied on an old building violation to prevent rural Los Gatos homeowner Sidney French, now 70, from repairing her 1930s-era cabin.

The document, from 1997, states her home was demolished and rebuilt without a permit. But even after French presented signed statements from neighbors attesting to it having been in its current form for decades, the Planning Department refused to budge and has even threatened criminal charges and exorbitant fines.

After additional experts looked into the case and advocated on French’s behalf, the County finally agreed a few months ago to expunge the mistake from her records.

French also filed an elder abuse complaint with Adult Protective Services against the County Counsel’s Office on Dec. 30. She took the extraordinary step after the department told her, 10 days earlier, it was declining to investigate complaints she’d sent in over how the department acts—or doesn’t.

However, her fight with the County continues, as she says it looks like they simply shifted the violation to another address, instead of eliminating it altogether, and adds the County is still refusing to remove the actual violations that she racked up because of the incorrect notations from 1997.

On Oct. 22, French added a new whistleblower complaint. She did this, she says, because her previous filings don’t resemble any in the latest transparency report to the Board of Supervisors.

As of Nov. 7, the report had not been posted to the County’s whistleblower portal.

French says last year’s didn’t appear there, either, until after she demanded the County put it up.

Agricultural Beginnings

The Katz brothers grew up in Morgan Hill after the family moved from San Jose.

“I spent my life there and watched the southern part of Silicon Valley become more urbanized,” Jesse said. “When I was young, there were strawberry fields around the house and people rode horses unironically.”

He has memories of watching the wildfire that consumed the mountain property he and his little brother would come to own.

“We would play in the forest out to the west in the Santa Cruz Mountains,” he said, telling of their early cycling and motorsport adventures. “I started working at the local Specialized bike shop when I was in 7th grade.”

Rob went on to study manufacturing engineering at Chico State with a minor in sustainability management. Jesse took classes in business, mechanical engineering, industrial design and marketing at a variety of colleges across California.

The brothers say they bought the Croy Road property, in part, to hold onto a little slice of the region’s agricultural heritage.

“We didn’t have any illusions about this being a profitable endeavor,” Jesse said. “It’s deeply hurtful to have Santa Clara County mischaracterize and portray us as bad actors.” Rob is technically the sole owner of the land, through an LLC.

The Katz brothers say the grading they did was appropriate because it related either to creating defensible space during and after the Loma Fire or was connected to agricultural activities they’d envisioned. They’ve argued some dirt-moving occurred prior to their ownership, and was simply laid bare after they cleared trees Cal Fire said they might want to remove.

They also say they’re happy to remediate their property, if they’ve done something wrong. Santa Clara County maintains the Katz brothers couldn’t have been attempting to farm, as they found little evidence of this. The Katz say they’d barely gotten started when the County forced them to put things on hold.

Family Farmers

A transcript of audio recordings of conversations with County staff, obtained by this newspaper, reveal that in the wake of the Stop Work Order, the brothers tried desperately to learn what sort of agriculture they could continue, but were shut down at every turn.

The County’s legal team told administrative hearing officer, George “Duf” Sundheim, that if the brothers were really planning to engage in agriculture, they should’ve brought this up during inspections.

However, the recordings transcript shows Jesse Katz told one of the inspection party—Craig Farley, of the South Santa Clara County Fire District—the exact location of a proposed root cellar, as well as the spot microgreens were to sprout.

In addition, they told multiple County officials of their designs for growing grapes.

“One question we have is, whether we would be allowed to resume our agricultural endeavors after this inspection, because I have like, 3-400 grapevines that like, if I don’t get them in the ground in the next couple weeks, we’re fucked; and I’ve already lost the whole season’s worth of seasonal agriculture,” Jesse said.

“Our vintner’s been holding these for us, and he’s like, ‘You have to get them into the ground right now.’ But the thing is that all that terracing below the emergency landing zone is for those grapes, and I need to do more dirt work before we can put those in.”

“Yeah,” County construction inspector Jerry Guevara acknowledges, per the transcript.

“All the hay needs to get scraped off,” Rob says, “because the hay can’t be in the grapes.”

“I understand resolving this red tag code enforcement stuff might be a big process, but if we could be allowed to resume our agricultural endeavors,” Jesse chimes in, “It’s an extreme hardship for us to be in suspended animation since November.”

Ward Penfold, of the County Counsel’s Office—who earlier in the day told the brothers his own distant relatives run the famous Penfolds winery in Australia (“That Grange stuff is really expensive,” he commented)—appears to completely brush off the viniculture remarks, as they gathered evidence for their prosecution. “We’re just gonna have to circle-up with the team after the inspection and all,” he said.

It’s unclear why this audio was excluded, as the inspection took place outdoors and so the conversations likely wouldn’t have carried the same expectation of privacy. In fact, in the ruling nixing recordings (that weren’t voicemails), the hearing officer states California’s current standard is “whether a participant to the communication reasonably expected the communication was simultaneously overheard or recorded.”

Ironically, in his decision, Sundheim agreed a recording of a marijuana dispensary raid would be admissible, as officers executing a search warrant would have no reasonable expectation their conversations weren’t being overheard or recorded.

Just this past January, Randall Zack from the County Counsel’s Office, sent a transcript of all the surreptitious recordings containing mysterious green highlighting to the Office of the County Hearing Officer and the Katz’ lawyer—while cc’ing County lawyer Michael Rossi and Code Enforcement Manager James Stephens, as well as the Board of Supervisors clerk.

The version the Katz brothers’ lawyer sent had been clean.

Zack is now a deputy attorney general with the California Attorney General’s Office. He didn’t respond to questions about this email, or the Katz brothers’ case.

Many of the green passages in the County’s version direct attention to quotes seemingly most damaging to the brothers’ case (such as how Jesse tells code enforcement officer Tyson Green “our strategy has been to hope that we can fly under the radar for long enough that if and when any enforcement action comes against us, we’ll be able to substantiate our intent, and show good faith, and show the progress we’ve made.”)

However, other highlights show the Katz sharing their ideological views on integrative agriculture with the County, including where Jesse discusses (with Green) their desire to create “more of a living landscape and a revitalized forest where people can be more in harmony with nature in ways that is a productive use of the land.”

In another quote from the first inspection, Rob mentions to Guevara how excited they are to have a south-facing slope to work with.

Jesse said this is an example of them explaining to the County about the site’s agricultural properties. “If you’re on a shaded, north-facing slope, you can’t grow the same types of things,” he said. The green highlight suggests County Counsel was aware of this too, and flagged it as an area of concern, in case Sundheim, former chairman of the California Republican Party, chose to admit the transcript.

In an April 11 letter to the hearing officer, the County was still using the fact that the brothers hadn’t been doing “in the ground” farming—something they believe they’ve been prohibited from—as a reason their trucks shouldn’t be considered agricultural vehicles.

But when County witness Darrell Wong, a civil engineer, was asked on the stand about whether they considered if the brothers had farming plans, he confirmed they never did.

“When you go out to a property and you see grading activity that clearly violates the ordinance code, are you in the habit of asking the property owner about every single exception to see if it applies?” Katz’ lawyer, Donald Sobelman of San Francisco-based Farella, Braun + Martel, LLP, asked.

“I do if it’s brought up,” Wong said. “But in this case—with both inspections—there was no exemption that was ever brought up.”

The County got a warrant that allowed it to search the Katz’ shipping containers, yet staff apparently never bothered to peer inside. The brothers say since they were no longer allowed to disturb the ground, the shipping containers were the main place they could continue to engage in agricultural activities.

The County’s own photos show vegetation poking out from one container, and planters with growing items placed on top of—and along—others.

At the administrative hearing, County Counsel argued it was the brothers’ responsibility to proactively direct the inspectors’ attention to the inside of each container if they wanted to be granted an exception.

‘I think there’s some inherent flaws in the way we do things out here’

—Tyson Green, code enforcement officer

Photos the Katz brothers placed into evidence depict a variety of agricultural uses from seed germination to squash growing. The Katz’ lawyer brought this discrepancy up while cross-examining code enforcement officer MaryEllen Luna.

“It could be the case that every one of those cargo containers was being used for agricultural use,” he suggested.

“Possibly,” she replied. “I did not look inside them.”

Sobelman asked if the Stop Work Order would prevent the Katz from doing agriculture.

“You can plant stuff, but you cannot continue to grade,” she said.

The brothers say they still needed to do more earth-moving before they could conduct agriculture on a commercially-viable basis.

“Kangaroo Court”

The Katz brothers were worried they might face a “kangaroo court” long before they got to the administrative hearing. After all, it was County employees who warned of underhanded behavior in the department.

Early on, Tyson Green, the code enforcer, sought to build a rapport with Jesse and told him how, as a Planning Department neophyte, he actually follows procedures—unlike others in the office.

In a March 11, 2019 call—three-and-a-half months after he’d first reached out (and three months since he’d left a message on department head Jaqueline Onciano’s machine)—Jesse complained to Green about a lack of communication from the Planning Department. According to Jesse, after the Stop Work Order appeared, it took more than a month to even get in touch with the County.

At the time, the Katz brothers were telling the County they had an opportunity to help them eliminate an illegal pot farm on the property next door (the neighbor was willing to give them the land for free), a proposal the County doesn’t seem to have followed up on.

“I think there’s some real inherent flaws in the way we do things out here,” Green tells Jesse. “If I issue somebody a Notice of Violation, I’ve got my contact information on there…and I’m required—within two days—to get back to somebody…I operate by that philosophy…I will tell you though, that that is not the standard operating procedure of most people around here.”

The brothers eventually managed to get a voluntary site visit scheduled, but as the date approached, Jesse shared with County staffer Michael Meehan that he felt like Penfold, of the County Counsel’s office, had taken an unnecessarily adversarial tack.

Meehan, who didn’t respond to interview requests, reminded Jesse that his colleagues weren’t to be mistaken for friends.

“What’s important for you to know is that—to be quite frank—they have everything they need to totally fuck you on this,” he said. “County Counsel has the authority to basically employ a receiver to take a loan out on the value of your property, remove you from the property, remedy all of the grading violations—at cost to you—and then also bill you for every minute that they spend working on it.”

He urged them to get into a compliance agreement.

“We need to be allowed to go back to our agricultural endeavors, or we’re gonna miss this whole season, and all the money that we’ve invested in these vines,” Jesse said.

Meehan cautioned that their attempts to reason with the County were falling on “deaf ears,” as the legal arm of Silicon Valley’s regional government built a case against them.

“They don’t want to hear anything,” Meehan said in the April 19, 2019, conversation. “They just want to show up. And so, the more information you give them, they’ll take it as hedging. You know what I mean?”

He told Jesse to speak to James Stephens, the code enforcement manager.

Jesse replied that it was the first time he’d ever heard that name—more than five months after the initial Stop Work Order appeared.

Meehan said he’d actually talked to Stephens just the day before about their case—and, boy, was he ever pissed. “He was upset that you hadn’t reached out to him,” Meehan said.

“I’ve never heard this name before,” Jesse reiterated. “Nobody has given me this name as a point of contact.”

Meehan suggested the best approach for the Katz brothers might be to apologize and claim the communication breakdown was their fault.

“He’s basically been reading all these emails and is like, ‘If this guy wants to comply, I’m the person to talk to. And he hasn’t talked to me,’” Meehan said.

“How would I know that, though?” Jesse asked. “I don’t know this process, and I only have the information I’ve been given.”

Meehan explained that Stephens—in charge, at that point, for less than a year—was taking a stricter line, particularly about violations in farmland.

“In some ways it’s great,” he said, noting there were some delinquent construction yards that did need to be dealt with. “No one has been doing anything about that, and he’s really cracking down on them.”

In late 2020, the Katz hired Gary Rudholm, a former Planning Department employee of two-and-a-half decades, who sought a meeting for the brothers with his former employer.

He told the Los Gatan his first step was to go to the front counter to get general information about the grading violations and the steps involved in fixing them.

Because of the raging coronavirus pandemic, the meeting was to occur virtually.

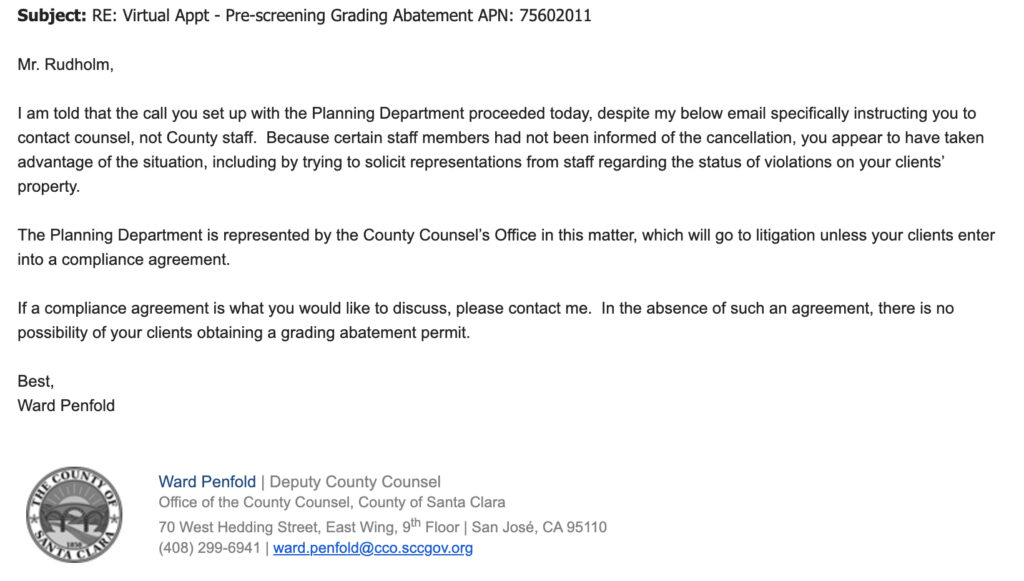

Rudholm was surprised Penfold, the County lawyer, somehow got wind of this and stepped in to try to prevent staff from having this public-facing conversation.

“I thought that Mr. Penfold was exceeding his authority by trying to cancel a meeting that I had set up to talk to the planner-on-duty at the County,” Rudholm said. “He is not the boss of the staff in the Planning Department. He doesn’t cancel their meetings.”

When Rudholm kept the appointment and logged on to the call, he was blindsided by several County heavyweights—including head geologist Jim Baker and Wong, the civil engineer—with code enforcement officer Green taking the lead.

Rudholm reminded them that “prescreening meetings”—where applicants and staff have a preliminary conversation to clarify requirements—used to be popular.

Wong said things had changed, but agreed it could still be a good approach, Rudholm recalled.

Then, at 6:03pm that night, Penfold stepped in and put the kibosh on any de-facto mediation.

“I am told that the call you set up with the Planning Department proceeded today, despite my below email specifically instructing you to contact counsel, not County staff,” Penfold wrote in an email. “If a compliance agreement is what you would like to discuss, please contact me. In the absence of such an agreement, there is no possibility of your clients obtaining a grading abatement permit.”

Penfold, who is now a commercial and white collar defense litigator at Latham & Watkins, did not respond to a request for comment.

At the administrative hearing, the County would explicitly claim the brothers didn’t ever try to fix grading issues on their land.

Zack, the County lawyer, even attempted to shut down attempts by the Katz’ counsel to talk about the meeting, describing the details as “irrelevant” to the hearing.

“You’re asking for very severe penalties,” the hearing officer said. “You’re saying they’ve done absolutely nothing to mitigate. So, to me, okay, that’s your argument. I want to hear if that’s accurate.”

Sobelman, the brothers’ lawyer, proceeded, asking Wong if he was aware of the communication from Penfold.

“I don’t recall it,” he said.

He also said he didn’t remember anything about what happened during the meeting, either.

Ironically, Rudholm says it was Green who pushed for a new meeting where grading violations, as well as building and zoning infractions, could all be addressed at the same time.

“What ended up happening is basically nothing,” Rudholm said. “Mr. Green did nothing.”

French says this episode in the Katz brothers’ saga echoes what happened with her: a scheduled meeting with Planning staff was abruptly changed to a hearing with code enforcement officers and lawyers at the last minute—without proper notice.

“They bait and switch,” she said. “We were called into a meeting with the code enforcement program manager who announced at the beginning of the hearing that he was making a determination on the (building violation) that was recorded in 1997 that he was opposing.”

Worse yet, she says, Deputy County Counsel Stefanie Wilson, who was representing the other side at the hearing, was put in charge of fulfilling her public records requests.

According to French, Wilson didn’t produce what she was seeking, and her whistleblower complaint (claiming it was inappropriate for an opposing lawyer to handle the records request) went nowhere (she points to a County policy stating this sort of issue should’ve been handled by an outside party).

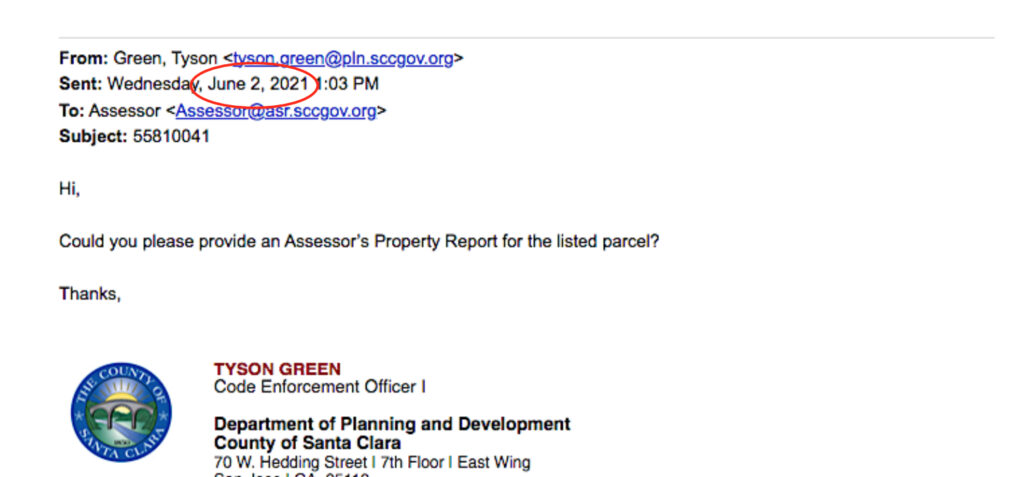

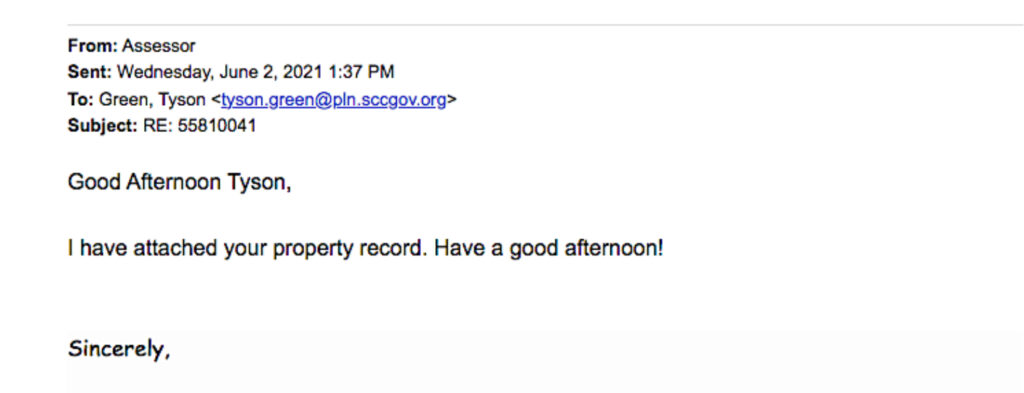

Neither did her whistleblower complaint claiming an inspector trespassed on her property (which she says she saw with her own eyes), or the one about how she believes Green illegally accessed her assessment records.

But the thing is the Santa Clara County Office of the Assessor sent her the email they got from Green, dated June 2, 2021.

“Could you please provide an Assessor’s Property Report for the listed parcel?” he asks.

Half an hour later, the Assessor’s Office staffer sent him French’s property info.

French is crying foul, pointing to sections of California law that say building officials and code enforcers aren’t allowed to snoop in these sorts of property files.

“A code enforcement division of a county’s building department is not a ‘law enforcement agency’ within the meaning of Revenue and Taxation Code section 408(b), to which assessors’ records must be disclosed,” reads a rule on the State Board of Equalization website.

Green didn’t respond when asked, by email, if he had some legitimate reason to be digging into French’s assessment file. He didn’t answer questions about the Katz brothers case, either.

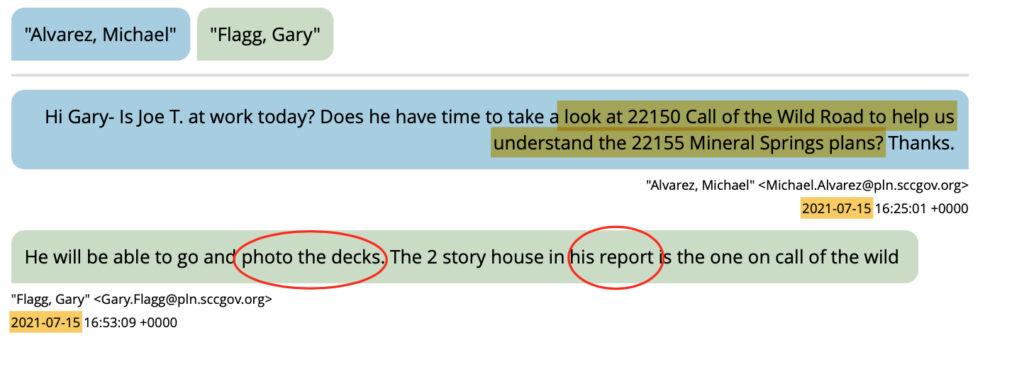

French also got her hands on a July 15, 2021 message exchange where Planning Department official Michael Alvarez asks Gary Flagg, a building inspector, to send “Joe T.” [apparently Joe Takacs, another inspector] out to her property—”to take a look at 22150 Call of the Wild Road to help us understand the 22155 Mineral Springs plans?” and Flagg responds “He will be able to go and photo the decks. The 2 story house in his report is the one on call of the wild”.

She said neither she nor her neighbor gave permission, and points out she has a “NO TRESPASSING” sign posted in a visible location along her driveway.

Realtor Madlin Betkouchar got involved after reading a Los Gatan article about French’s situation. She spent hours looking into the case—blowing off personal engagements to discuss the details with French—and the more she learned, the more she was convinced the County was acting inappropriately.

She ultimately had a falling out with French, finding her difficult to work with. However, before they parted ways, Betkouchar said she took Planning Director Onciano to task for the department’s behavior. “I said, ‘Your job over there is to help people,’” Betkouchar recalled, suggesting there’s too much “corporate dirty work” going on. “I said, ‘How would you feel if you are escorted out of your department if you’re found out to be responsible?’” Betkouchar says she remembers a time, years ago, when someone else she was working with faced mistreatment by the Santa Clara County Building Department. “They actually played favoritism,” she said. “People take things personal, and it shouldn’t be. They need to separate their personal feelings from the professional ones.”

Onciano declined multiple requests for an interview and referred inquiries to the media relations office. The Los Gatan sent in more than 30 questions including asking about the alleged trespassing and failure to have an outside party investigate a whistleblower complaint against County Counsel, as well as about the Katz brothers’ case, but the communications team refused to respond to most of them.

“While the county does not provide detailed information about ongoing code enforcement matters, we want to underscore the county’s willingness to work with all residents to abate violations, and consistent with that practice, the county expunged the historical building code violation recorded on Sidney French’s property on June 23, 2023,” the said in a statement. “As for your other questions, the county does not comment on personnel matters.”

Rudholm felt Green’s explanation for why the County took a strong line against the Katz brothers, during the December 2020 meet, was noteworthy.

“When I asked Mr. Green why County Counsel became involved in this enforcement case ‘early on’ he explained that he had gone to the property for an inspection and was met in the field by Mr. Jesse Katz along with Mr. Katz’s attorney,” Rudholm said in a letter documenting the meeting. “Mr. Green said that because Mr. Katz had an attorney representing him at that time it became necessary for Code Enforcement to bring in County Counsel.”

But Jesse swears he’s never met Green in person.

“Tyson wanted to go straight to the attorneys instead of dealing with the professional staff in the Planning Department,” Rudholm told the Los Gatan. “I was surprised.”

Midway through, Green told Rudholm he better not be recording, as that would be a felony.

Rudholm says he agreed to assist the Katz brothers because he appreciated their passion for developing their property in a dynamic way, and thought he could help translate this enthusiasm into language the County might understand. But eventually he gave up trying.

“I felt I was just pounding my head against the wall,” he said. “I didn’t know what next to do.”

Later, when he saw an unsigned compliance agreement from the County, it contained wording that would permit authorities to confiscate the Katz brothers’ land if they deviated from the work plan one little bit.

“The fine is one thing,” he said. “The clause allowing the County to seize the land is different.”

Civil Rights Dimension

Travel up the twirling dirt road to Gatos Gardens and it’s clear why Army gear would be ideal for the terrain—this reporter’s car became temporarily stuck in a rut at the entrance to the property.

The view is magnificent. To the east: Silicon Valley bedroom communities. To the west: a landscape suggestive of America’s settler days, complete with trailers and humble structures scattered amid a hearty evergreen forest.

There’s a sense of unbridled possibility, a feeling you can still do whatever you want, away from the watchful eyes of the authorities.

Pull into the driveway and you’re greeted by a flat, shaded space, and a rusting, ornamental piece of heavy equipment—a vestige of a rapidly-fading way of life.

It’s just like many of the rugged estates sprinkled across California where an idealistic traveler might find themselves working for a month or two after applying on an organic farming opportunities website.

There’s an outdoor shop-type area to the right, where strange vehicles loom large around the edge. Further down there’s a section ringed by trampolines and more shipping containers.

You can’t help but see how it would make for an ideal place to hang, discussing the latest permaculture theories, after a day of hauling materials and tending to terraces.

The side of one container is painted white, apparently to double as a movie screen. Antennae and communication dishes make the property look like an emergency command post, especially since there’s a landing pad up the hill, with a plastic square containing liquid, and snakes of fire-retardant material, inside another huge metal box.

To hear the County’s arguments about illicit military vehicles, landscape alteration and noncompliance, you might be left with an image of a couple rednecks raising their own private militia, in footsteps of federal-government-sparring Ammon Bundy.

But way back in October 2017—long before litigation with the Planning Department was in the offing—they posted on their GatosBros Facebook page offering to “host evacuees and refugees” affected by fires in Northern California and hurricanes “—Immigration status irrelevant.” This suggests a more liberal mindset pervaded the land called “CroixPines Sanctuary” at the time.

They specified they only had five campsites to offer, “but we do have additional space available if you are interested in work/trade.”

It’s unclear what work the County thought this potential labor force was to be engaged in, if not agriculture or wildfire prevention, though the page, started in August 2012, is listed as for an Outdoor & Sporting Goods Company.

In the administrative hearing Luna, the code enforcement officer, said it was clear the Katz’ large vehicles couldn’t be stored on their property because they reminded her of something you might see in a “military movie.”

The Katz say it’s just cheaper to score surplus military gear than to buy used PG&E trucks or John Deere tractors. And they say there’s something symbolic about taking something designed for the theater of war, defanging it, and placing it in service of something more positive—like fire prevention or agriculture.

Over the years, Jesse’s social media activity has indicated the connection he sees between farming and activism, including via a June 2017 Facebook post of a realfarmacy.com article titled, “Why Growing Food is The Single Most Impactful Thing You Can Do in a Corrupt Political System.”

The piece, by Alex Pietrowski, originally published by Waking Times, celebrated people like Ron Finley, the so-called Los Angeles ‘Guerrilla Gardener,’ and Marc Angelo, who now operates an 88-acre farm on the south shore of Montreal called Valhalla Farms.

It was actually the County that submitted this piece of evidence.

“The simple act of growing our own food directly challenges the control matrix in many authentic ways, which is why some of the most forward-thinking and strongest-willed people are picking up shovels and defiantly starting gardens,” Pietrowski wrote.

The Planning Department didn’t take too kindly to the Katz Brothers standing up for what they perceived to be their rights.

And earlier this year, a free speech activist found Planning Department headquarters itself, in downtown San Jose, to be quite the unfriendly place, during an unsolicited inspection.

The film crew for the YouTuber Anthony X’s channel, who conducts so-called First Amendment audits of various public facilities to check for violations, was assaulted—unprovoked—by a security guard, as Onciano, pleads with the man not to escalate things.

“I’ve been to that building a few times and it’s horrible the way they treat citizens,” Anthony X told the Los Gatan.

The footage appears to show the planning director herself getting assaulted by the out-of-control guard. When asked, the County declined to say if it offered Onciano any mental health resources in the wake of the on-the-job violence in her department.

In the upload, Anthony X tells the department head there’s nothing indicating he can’t wander around recording video and examining brochures meant for members of the public.

Onciano asks him why he didn’t just ring the bell to get someone’s attention.

The YouTuber, still in a chipper mood, points out it was hidden.

On April 17, 2017, the very same day Jesse had a conversation with Deputy District Attorney Jason Malinsky, a Los Gatos resident per his Linkedin page, about a criminal charge he was facing, Sheriff’s Office deputy Frank Thrall drove onto a private road to confront him about not having a license plate on his truck.

“Am I being detained?” Jesse asks, in the filmed encounter.

“Yes,” Thrall says.

“You have no right to be here right now,” Jesse admonishes. “You do not have a right to patrol private residences.”

“Yes, we do,” Thrall retorts, stating he’d photographed Jesse drawing water from the creek. “I have a right to stop somebody when I believe there is criminal activity afoot.”

Jesse tells Thrall multiple times about the property documents (which he shared with the Los Gatan) that grant the Katz riparian rights.

Finally, the deputy agrees to leave.

In 2014, the Katz were eating at a taco restaurant in Barstow when a man accused them, and others, of stealing a vaporizer, then called police.

Rob and Jesse were charged for refusing to identify themselves to law enforcement, but the ACLU of Southern California intervened on their behalf.

“The brothers had done nothing wrong and exercised their right to refuse to show ID,” the ACLU later wrote in a blog post. “The officers arrested them and took them to jail.”

In the end the charges were dropped, and in 2015 the brothers won a $15,000 settlement (each) and Barstow police agreed to distribute a training bulletin about the right citizens have to refuse to show ID in many situations.

A Morgan Hill Times report about the time Jesse was arrested and charged in 2017 for the exact thing—refusing to show ID—revealed police reacted with greater intensity due to the brothers’ “anti-police” stance, with law enforcement pointing to the Barstow arrest as proof.

The Morgan Hill Police Department even denied the newspaper’s request for body-worn camera footage of the incident.

Jesse sent the Deputy District Attorney Malinsky an email bringing him up to speed on their legal victory in SoCal.

“I worked with the ACLU to draft new policing guidelines and a training bulletin that is now distributed to every law enforcement officer in Barstow, advising officers as to how they must respect citizen’s rights related to presenting officers with ID,” Jesse wrote.

And so, the day following Katz’ contentious interaction with Deputy Thrall, he got positive news from the Santa Clara County DA’s office.

“Your case will be dismissed in the interest of justice at Wednesday afternoon’s court appearance,” Malinsky wrote, though he told Morgan Hill Times police didn’t err by making the arrest in the first place.

Jesse followed-up by sending a copy of the policy Barstow officers now receive, urging the prosecutor to “Educate law enforcement officers on this subject.”

Thrall would continue to be a thorn in the Katz brothers’ side as the code enforcement investigation ramped-up.

Jesse begged for there to be no police presence at one inspection. And if a cop had to come, could it please be someone else—anyone else—besides Thrall?

Who showed up? Thrall.

The brothers are sure the County did this just to stick it to them.

A July 16, 2018 email—from Thrall to code enforcement officer Luna (revealed through a Public Records Act request)—titled “Photos of the Katz property,” included photos that appear to have been taken of the Katz’ property—from the Katz’ property.

“I hope these help,” he wrote.

Jesse says this proves Thrall trespassed, again, on private land, and disproves Luna’s claim that it was the Katz’ lack of response to a County letter that turned up the heat against them.

The brothers’ freedom of information request never did reveal this supposed letter.

Thrall popped up again, months later, threatening to arrest Jesse for trespassing on a neighbor’s property, despite documents that appear to show an easement granting them a right-of-way.

The big Nov. 16, 2022, administrative hearing—four years after the original Stop Work Order was issued—took about six-and-a-half hours.

Prior to this, the County’s secretive process had finally afforded the brothers just a fraction of that to present their situation.

They’d even had to hire their own court reporter for it to be properly documented.

“Did any of the County attendees provide any information in that meeting about the basis of the violations?” Sobelman asked Rob, during the administrative hearing.

“None,” he answered. “And it was, honestly, far too short. We had less than an hour to go through everything before the meeting was cut off.”

Rob added that it was essentially just his brother talking as officials listened.

“And did any of the witnesses who testified for the County today present any information at that hearing to support the allegations?” their lawyer asked.

“No, they did not,” Rob replied.

The Katz brothers say it seemed like the County was simply interested in cracking down on them and had no interest in working out a solution.

The County notes after the meeting they removed violations, which they say proves the soundness of their process.

Over the years, the County kept moving the goalposts—and then tried to prevent evidence of this from making it into the public record, the Katz brothers say.

At first, a code enforcement officer told them they weren’t allowed to do any agriculture on their property whatsoever, since they live in a hillside zone.

That was quickly disproven.

‘It just has felt like the County is throwing allegations at us, hoping something sticks. And it is incredibly painful and expensive to have to rebuff all this.’

—Rob Katz

In a May 19, 2019, phone call, just after an inspection, Wong told Jesse that an agricultural exception wouldn’t apply.

“Why is that?” Jesse asked.

“I mean for one, it’s not allowed in landslide hazard zone,” Wong said. “And I’m pretty sure you are in one.”

So, the Katz brothers looked it up.

“Immediately, it was clear that we’re not—per the County’s own maps,” Rob testified at the administrative hearing. “So, it just has felt like the County is throwing allegations at us, hoping something sticks. And it is incredibly painful and expensive to have to rebuff all this.”

All of the sudden, County Counsel Michael Rossi broke in.

“I’m going to impose an objection here,” he said. “The County never said that—I didn’t hear any testimony to the point that the property was in a liquefaction zone.”

Luckily, the hearing officer was on the ball and noticed Rossi incorrectly undermining Rob’s testimony.

“He’s just talking about an example of his interaction with them in the past, that they made certain assertions that he believes were incorrect,” he said. “It’s not hearsay or anything.”

By this point, the County was claiming the property was too steep: a 30-40% slope, when the maximum that would allow for agricultural earth-moving is 20%.

In his testimony, Rob said he used the County’s own data to prove that the actual areas that they graded had nowhere near a 20% slope.

They submitted evidence—using Guevara’s notations—to indicate slopes of 14.7%, 13.9%, 8.6%, 7%, 25%, 19.2%, 11.8% and 12.7% on various sections of their land.

Cal Fire Santa Clara County Unit Forester Ed Orre, who testified for the brothers at the hearing, told the Los Gatan the graded area he saw had a “relatively gentle slope.”

He was one of two Cal Fire officials who testified on their behalf.

It made sense to Orre that the brothers created defensible space during a massive wildfire.

“They were one of many other landowners who were scared,” he said. “They took out hardly any trees there.”

He adds that, if you consider the overall picture of what’s going on in the Santa Cruz Mountains—for example, people growing cannabis illegally—what the Katz brothers did was pretty inconsequential.

“The area they cleared is not striking compared to all the other sites,” he said, when asked about the County’s enforcement behavior. “They were definitely very hard on them.”

It wasn’t like the Katz were trying to change forestry land to a farm—something you’d need a conversion permit for, he added, noting he personally counseled the brothers to thin-out the knobcone pine that grew up in the wake of the prior wildfire.

“Knobcone’s extremely flammable,” he said, confirming that he said a clearing they made could be useful to Cal Fire as a helicopter pad, probably not regularly, but perhaps in an emergency.

It was the Katz brothers who actually taught Penfold about the fire danger of knobcone stands during that first, voluntary, inspection.

Does Orre think the County’s crackdown on the Katz brothers was fair?

“No,” he said. “I don’t. Especially in context.”

The brothers say the enforcement has had a crushing impact on their personal lives.

“It’s been tremendous,” Rob said at the conclusion of his testimony. “It has ruined a relationship of mine. At one point, I was engaged—and I’m no longer. And I’m certain that, in no small part, that was because of the issues happening here. It put a strain on my personal relationships. It has been a nightmare in every way.”

Fire Defense Exemption Argument

Another Morgan Hill-area resident, Jen Cybart, 50, who’s been following the Katz brothers’ story, says her family’s caught up in a similar situation—after making a path to clear deadfall from their 12 hillside acres.

“We did fuel reduction on our property,” she said, telling the Los Gatan, Oct. 20, she’s still waiting for a Notice of Violation to arrive. “If you can’t protect your house—to have defensible space because they don’t allow for it—it’s basically the same as not having a speeding limit on the road and then you get a ticket.”

She’s been meeting with Santa Clara County officials, urging them to adopt policies similar to other counties, like San Luis Obispo, which she says are more forward-thinking in terms of wildfire preparedness.

Cybart built her own house, so she’s familiar with the Planning Department, including civil engineer Wong.

“Darrell is kind of notorious,” she said. “His hands are tied to the ordinances.”

He’s already given her a preview of what’s coming.

“‘You’ll have to pay me $8,000 up front,’” she says he told her. “‘You’re going to have to put all that dirt back.’”

Wong didn’t respond when asked about the $8,000 figure.

Cybart has been speaking with State fire officials, including with Board of Forestry and Fire Protection Executive Officer Edith Hannigan, and the Fire Marshal’s Office, and this has convinced her Santa Clara County is behind the curve in preparing for the predicted increase in wildfires.

“You need to harden your home, and harden your property, and provide defensible space, and access on your property, and there should be no questions asked by any grading department—ever—because of this,” she said. “I think the real story here is…a government entity is being onerous to the negative impact of a homeowner—especially in regards to fire.”

In her case, the County told her an exemption might apply if she can prove the grading happened over time, and not all at once.

“What’s really stupid about it is, they want more pictures of dirt from my past,” she said. “Who goes around taking pictures of dirt?”

Luckily, she and her husband got poison oak at least 10 times while doing the property hardening work, so she’s been snapping photos of medicine bottle dates.

“So, you’re in violation because of the antiquated ordinances,” she said. “It’s just ridiculous.”