Two developers trying to build a significant amount of housing in Los Gatos have fired back at the Town in court, accusing it of illegally blocking the development of homes—including affordable units.

This comes after the Town took to Santa Clara County Superior Court seeking a ruling against Sacramento’s approach to dealing with temporarily delinquent municipalities such as Los Gatos—referred to as “Cross-Defendants” in the developers’ filing.

“In the midst of a severe housing crisis gripping the state of California, Cross-Defendants are flouting their responsibilities to process housing projects that are protected by state law,” wrote Matthew C. Henderson, of Walnut Creek-based Miller Starr Regalia, the lawyer for Arya Properties, LLC and Los Gatos Boulevard Properties, LLC, April 25. “This case arises from Cross-Defendants’ bad faith attempt to rob Cross-Complainants of vested rights under California law to develop housing projects with low-income homes.”

Unlike the City of Scotts Valley, which submitted an acceptable homes plan essentially within the allotted timeframe, Los Gatos and Monte Sereno were out of compliance for more than a year.

This triggered the “Builder’s Remedy” mechanism, which allows developers to come in with projects they normally couldn’t normally build, which municipalities are required to rubber-stamp, provided these include a minimum amount of affordable housing units and don’t cause serious health and safety issues.

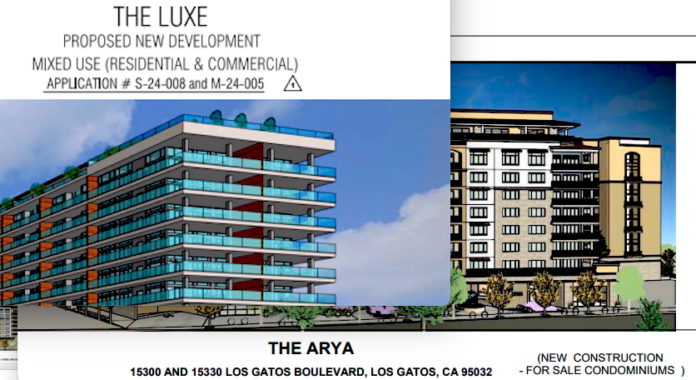

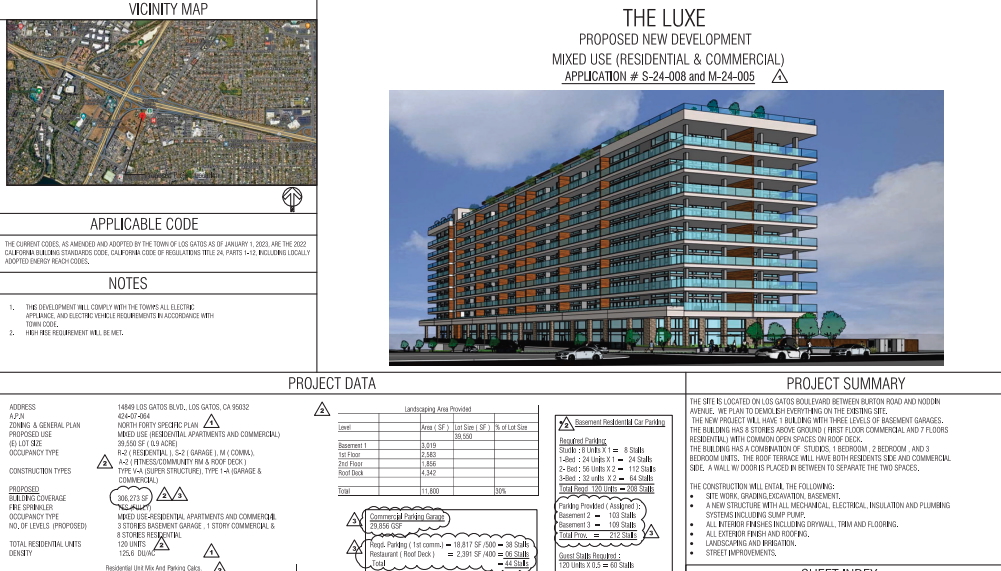

Both the Arya Properties and Los Gatos Boulevard Properties brought their multi-family projects in under this rule, much to the chagrin of neighbors. Both are about nine stories (depending on how you count the rooftop amenities).

“The Arya” is better known to many locals as the “Ace Hardware” project, because it envisions placing a highrise at the site of one of two Ace Hardware locations in town, at 15300 and 15330 Los Gatos Blvd. Meanwhile,

LGBP refers to a tower for the North 40 Specific Plan area (14849 Los Gatos Blvd.), but which isn’t part of the main North 40 Phase 2 project by Grosvenor.

The Town’s website currently states that both applications are “incomplete.”

Many locals blame not the local politicians who caused Los Gatos to fall out of compliance with the housing law by fighting Housing Element changes demanded by the Department of Housing and Community Development, but the developers who took advantage of the incentive.

And now, Los Gatos’ latest tactic is to fight the Department of Housing Development’s pronouncements—not by suing them directly, but by questioning its interpretation of State law in the civil action it brought against Arya Properties and Los Gatos Boulevard Properties.

Los Gatos is hoping it can get a judge to agree that Builder’s Remedy projects only have a short window to fix problems with developments identified by Town planners. However, the developers say the State has been clear that it can have multiple opportunities to improve supposed issues with its plans.

They say the Town “wrongly asserted that Cross-Complainants’ vested rights relating to the projects were expired and unenforceable,” adding the lawsuit itself limits its rights under the Housing Accountability Act.

“As recognized by the California Legislature, the current housing crisis is driven, in part, ‘by activities and policies of many local governments that limit the approval of housing, increase the cost of land for housing, and require that high fees and exactions be paid by producers of housing,’” Henderson wrote.

“Such is the case here, where Cross-Defendants’ pattern of conduct includes, but is not limited to: (1) attempting to subvert the (Permit Streamlining Act) and SB 330 through arbitrary and bad-faith application procedures and policies; (2) ignoring state housing laws that permit low-income housing development projects when a local jurisdiction does not have a compliant Housing Element of its General Plan; and (3) denying housing applicants vested rights to which they are entitled under state law. These policies and practices are antithetical and antagonistic to the Legislature’s effort to address California’s ongoing housing crisis, thus necessitating the filing of this cross-complaint.”

The developers pointed the judge’s attention to what happened in Beverly Hills, which follows a Housing Element cycle that’s a couple years ahead of the Bay Area.

They attached a Dec. 2, 2024 letter to Michael Forbes, director of community development for the City of Beverly Hills, from David Zisser, HCD’s assistant deputy director, local government relations and accountability.

Beverly Hills was out of compliance from 2021 until March 2024 and attracted a number of Builder’s Remedy projects in that time.

In the letter, the bureaucrat put the planner on notice that Sacramento is not happy with the nearly 1,000 units in 10 projects blocked via one technique (the 90210 officials were trying to say builders needed to include a “General Plan Amendment and Zoning Change” document, even though it hadn’t asked for one).

“HCD also finds the City’s liberal interpretation of what may disqualify a project from the vested rights…to be problematic. Finally, HCD rejects the City’s claim that the PSA only provides one 90-day period for a developer to submit all of the information necessary for its full application to be deemed complete,” Zisser wrote, adding, “the 90-day period to submit information to complete a full application reset after each incompleteness determination, and the preliminary application remains vested during these 90-day periods.”

But the Town says it’s the government that’s breaking State law by forcing municipalities like Beverly Hills and Los Gatos to give developers more time to tweak their projects.

Town Attorney Gabrielle Whelan says HCD’s approach would do the opposite of the agency’s stated intention.

“The Town is concerned that allowing unlimited 90-day periods within which to complete the application will delay rather than speed up the production of housing in Los Gatos,” is how she put it in a March 27 letter to Travis Brooks of Miller Starr Regalia, one of the developers’ lawyers.

On May 27, Whelan went before Judge Vincent J. Chiarello to make that point.

She didn’t highlight the battles fought in Council Chambers over HCD’s contention that Los Gatos needed to do more to open itself up to economically and racially diverse populations when it comes to housing, or efforts to block mid-sized home options from large swaths of the community.

She put things in a much rosier light.

“Crucially, the Town has a strong record of housing accomplishments,” reads the statement that accompanied the hearing, adding Los Gatos has “gone beyond state requirements to encourage the development of affordable housing. In the past two years alone, it has approved applications totaling hundreds of units of new housing.”

The developers’ lawyers claim Los Gatos is using a “mistaken interpretation” of the HAA and PSA.

“Cross-Defendants have taken the position that the preliminary applications have expired and can no longer vest rights to proceed with the projects, which unlawfully denies Cross-Complainants and their projects the protections of the HAA,” they said in their statement.

On June 13, Miller Starr Regalia filed a notice informing the court of two related civil cases underway: Lixin (León) Chen, et al. v. City of Cupertino, et al. and Yes In My Back Yard, Chunhua Tang, et al. v. City of Cupertino, et al.

“In each case, the applicable municipality has taken the position that, pursuant to Government Code section 65941.1, subdivision (e)(2), an applicant for a builders remedy project must submit a complete development application within 90 days of an incompleteness determination or lose its vested rights under its preliminary application,” the developers’ lawyer wrote. “The applicants in all three cases reject this interpretation as improperly limiting the lifespan of a builders remedy project and giving cities and counties that want to kill such projects a ready means of doing so. While the facts of each project application are necessarily somewhat different, the fact patterns are essentially the same, and the dispositive legal issue in all three cases is identical.”