When Julia Ernsting, now 16, was in fifth grade, she was stressed out with more than just the daily grind of homework and tests.

That’s because she was frequently traveling up the peninsula to San Francisco to check on an immediate family member who had been diagnosed with liver cancer.

“Because they knew about the cancer early enough, he was able to get a transplant,” she said, remembering how intense the ordeal was, and how she did whatever she could to make his things more manageable for him. “They let me send in my favorite stuffed animal.”

Her loved one recovered, but the experience stuck with her.

Even as she earned a spot on the Los Gatos High School varsity water polo team, she began helping the campus football training staff, filling water bottles and doing preliminary taping.

Because as much as she loved the team aspect of conquering in the pool, she couldn’t let go of her growing interest in the possibilities of the medical world.

She wanted to understand the mysteries of the liver.

“I always knew I wanted to do research,” she said. “It was just a question of how to get my foot in the door.”

She reached out to Los Gatos Research Group, LLC, and embarked on a study that would probe the unknowns of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NFLD) in youth.

Many are aware that drugs and alcohol can wreak havoc on your liver.

However, NAFLD—a liver problem that can’t be attributed to such behaviors—is now recognized by experts as the most common cause of chronic liver disease worldwide.

Most of these patients have what’s called “simple steatosis,” a somewhat-harmless accumulation of fat in the blood-cleansing organ, though some face more serious consequences.

For the study to work, Ernsting had to convince a bunch of her friends, as well as total strangers, to go through an examination and respond to a number of personal questions—not exactly at the top of the list of potential extracurriculars for a teen.

‘I just thought of how much this could help other kids.’

—Julia Ernsting, Los Gatos High School student

Or, to put the endeavor in Ernsting’s words—“social suicide.”

Her dad, Kevin, remembers how the project hit a snag.

“At the beginning it was hard because she was trying to get people to go to the physician’s office,” he said. “People—especially at the beginning when her friends were younger—a lot of them didn’t drive.”

Julia was able to get certified to do the liver scans herself and secured permission from the school to complete on-site examinations of her fellow students.

“Some of them were scared,” she said, adding having a peer completing the research task seemed to put them at ease. “They had a friendly face doing it.”

Thanks to the assistance of people such as Jacob Rojas, the LGHS head athletic trainer, she was able to turn the corner and recruit a total of 83 people.

“I just thought of how much this could help other kids for screening, and how this could show a new side of fatty liver,” she said. “I was lucky to have people help me.”

In some ways, what lay ahead was the most difficult part.

Instead of the regular term paper challenges, she had to figure out how to develop an “abstract”—the introductory portion of a research paper that summarizes the findings.

“It was definitely a little bit stressful,” she said. “Writing the abstract was probably one of the hardest things I’ve done.”

She ixnayed social functions and spent hours on Zoom calls with her research mentor, working out the most efficient and precise way to characterize the data.

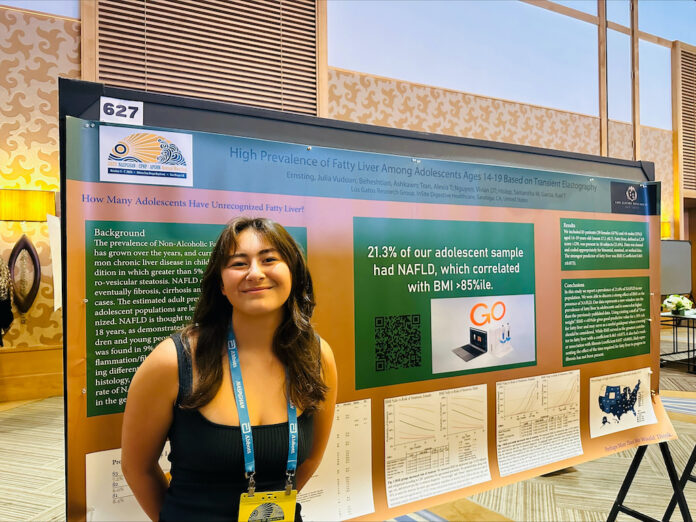

They submitted it to the NASPGHAN 2023 conference in San Diego, which is the first step toward putting the research out into the scientific world.

Then, on a Friday afternoon in August, she got an email from the co-chairs of the abstracts committee.

“We are pleased to inform you that your abstract entitled, ‘High Prevalence of Fatty Liver Among Adolescents Age 14-19 Based on Transient Elastography’ has been selected for poster presentation at NASPGHAN 2023,” it said. “Congratulations and we look forward to seeing you in San Diego.”

The fact the message’s salutation was “Dear Dr. Ernsting,” underlines how the pediatric gastroenterologists accepted her presentation on its merits, and not as a gimmick to add a plucky high schooler to an otherwise stuffy gathering of specialists.

Ernsting was elated.

“It was like getting into my dream college,” she said. “I actually got accepted.”

But now, this meant she had to develop the research into a poster that could be exhibited at the event.

“It was hours of me just sitting down on my computer and going into InDesign and working out every little detail,” she said, recalling how she had to put in charts by hand, because the original images were too blurry to look good at such a large scale.

She prepared her spiel, went over it again and again, and, over the weekend, headed down to San Diego for the first time in her life.

“I was so stressed the morning of; I woke up at 6am,” she said, remembering how she faced the mirror and ran through her lines, one last time. “I gave myself a little pep talk: ‘You’ve got this. You know everything.’”

Ernsting had nothing to worry about. Having been intimately connected to the data collection and synthesis, the words flowed freely and attendees were intrigued.

She started by reminding them how many people around the world are afflicted with NAFLD—around 10%—then shared how they discovered 21.3% of participants in their study (18 out of 83) exhibited this condition.

This was despite including many athletes.

“This was obviously very surprising,” she said.

While it wasn’t exactly earthshattering to discover that BMI—or obesity—is the main risk factor, their research suggested that students today could be in even greater danger of developing problematic livers than previously thought.

For example, she explained in the conference hall, earlier data points to the quarter of the population that’s most obese as being 50% more likely to develop steatosis.

However, their research suggests that it could be as much as the top 19 percentile that are half as likely to be diagnosed with the fatty liver condition.

“The more surprising part is if you’re only in the 61st percentile, and you didn’t exercise, you were also at a 50% more likelihood to have steatosis,” she said, recalling how attendees seemed to be listening intently. “They were all so sweet to me.”

Of course, every study has its limitations. And that’s been part of the learning process for Ernsting, too.

It was clear that as much of a success as it was to get nearly 100 teenagers to go through a liver scan, this would still be considered a smaller study in the grand scheme of things.

And Ernsting can think of minor changes she would make to minute details of the survey wording if she were to do it over again—perhaps adjusting the metric for what’s considered an active individual.

Nevertheless, she’s hopeful she’ll be able to develop the research into a complete manuscript for publication in a prestigious medical journal.

Of course, that means she now has a whole new task in front of her.

“I have to make time for it,” she said. “I really want to show other people what can happen. My research shows new information and I want to share that out. So, I’d love to write a paper.”

Her dad, an emergency room physician, is proud of the progress she’s made, so far.

“This is more than I did during my research career,” he said. “She’s got a leg up on me already.”

Plus, it’s been nice to see his daughter fall into something that she connects with.

“Being part of this larger research group allows her to find a place where she fits in,” he said. “It gives her a role to play.”

He says he only provided minor support along the way, like helping with copyediting.

But he knows just how serious liver afflictions can be.

It’s the end stages of liver disease that he ends up seeing in the ER.

However, he’s hopeful that with research—such as the project undertaken by his daughter—the murky area of science can find clarity and result in better outcomes for patients, earlier.

“That’s the goal,” he said, “—understand fatty liver as an early process, provide interventions and prevent progression.”

Whatever happens next, Ernsting says it’s been a beneficial exercise for the Wildcats who offered up their livers virtually for science, teaching them it’s possible to do this kind of science, for real.

“It’s also like, what do you want to give up,” she said, remembering the Friday nights she stayed in instead of heading out with her friends. “Anyone can do the research if you want to put the time into it.”

Very helpful information. I’ve been reading about how some students are taking research seriously, like that Los Gatos high schooler working on liver disease. It really inspired me, but honestly, I’m struggling to manage my own research paper. Is there a way I can pay someone to write or guide me through my research paper while still keeping it original and quality-focused like those real science projects?